What’s Blue Monday really telling us about ourselves?

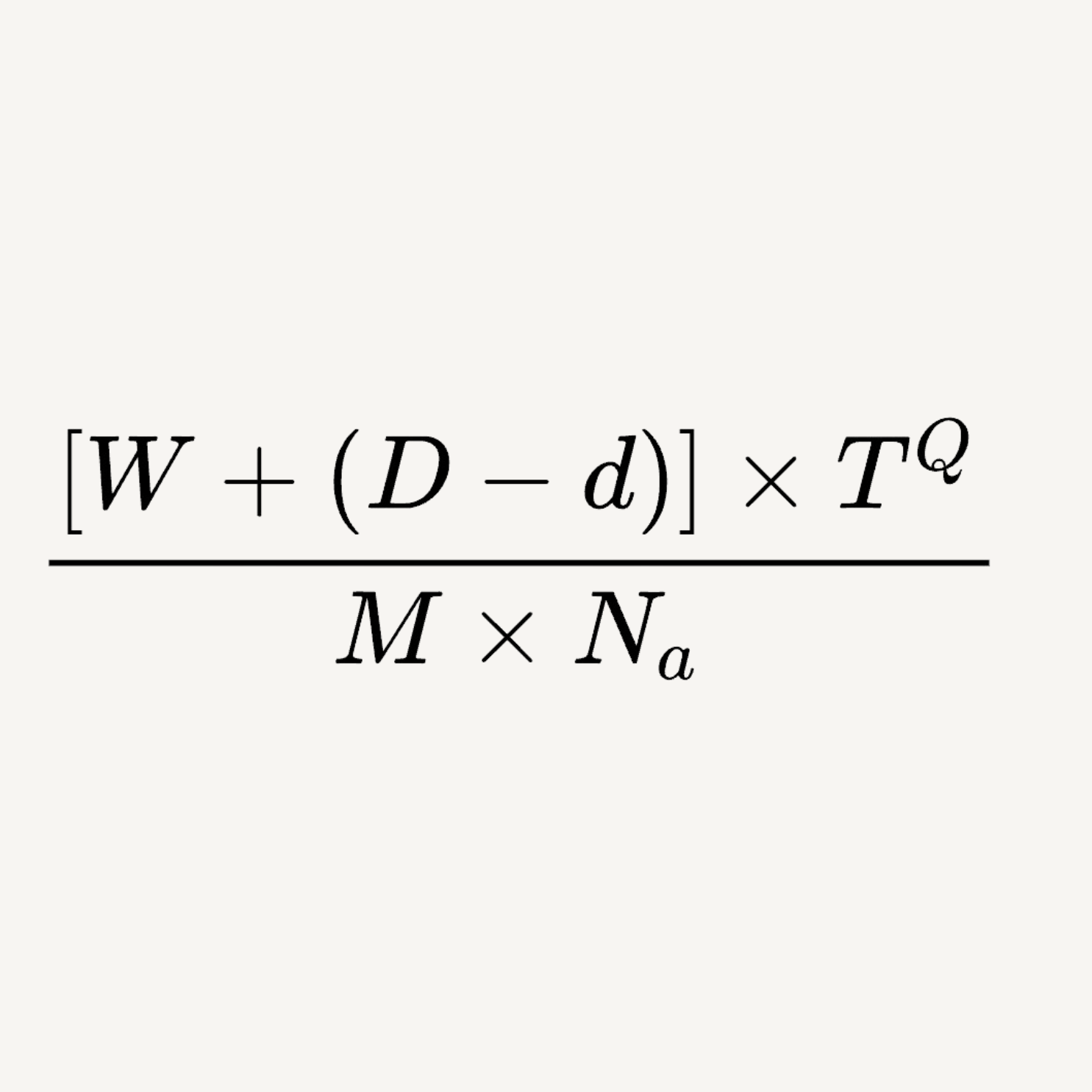

Does this equation look at all familiar to you? It’s the calculation used to explain why the third Monday in January is statistically the most depressing day of the year (you can find the equation explained here). The date was coined back in 2005, and is one that is firmly predicated on pseudoscience, as the man who named Blue Monday freely concedes. However, the date has leached into the public consciousness and become a fixture of public conversation.

Despite being little more than a social construct, it’s endured as a feature of January, likely because it resonates with people on multiple levels. It aligns statistically with the post-Christmas financial strain, compounded by the seasonal darkness, the post-holiday lethargy, and the fact that many of us are sitting with the self-loathing that comes from recently shattered New Year’s resolutions. This is then all amplified by media outlets (like the one you’re currently reading), which ensure that Blue Monday has woven itself securely into the fabric of contemporary culture.

While some mental health advocates have real concerns that Blue Monday trivializes depression, it does seem to provide a platform for dialogue and reflection on the challenges of navigating the winter months. The social prescriptions for combatting a low mood are now fairly well-known and are soundly established scientifically: physical exercise, sleep, social connection, limiting social media, setting realistic goals, and practising gratitude. These discussions are helpful in pointing out that we have agency and that there are actionable steps we can take that will improve how we feel.

In and of itself, this seems like a good and helpful provocation, though you could take the conversation a step further and ask whether Blue Monday is highlighting something significant in the human condition, whether, in some sense, it works as a compass for our deeper yearnings. In 2018, the journalist Johann Hari wrote a book about dealing with depression called Lost Connections. Hari looks at the environmental reasons that depression is so prevalent in modern Western culture – that we’re alienated from each other, from meaningful work, from the earth, and from our bodies, amongst other things. These are connections that we’re naturally wired for, and the lack of connection to these things can give rise to feelings of anxiety and depression.

Hari’s book is scientifically robust, and many have found it extremely helpful. By looking at those connections we’re made for, those facets of life that make us whole, you get a sense of the shape of the human soul. However, one very significant area that Hari is silent on is spirituality. This is somewhat baffling given the raft of research indicating how essential spirituality is to wellbeing. Lisa Miller, a professor of psychology at Columbia University in New York, draws on large-scale epidemiological studies as well as neurobiology to argue that people with a spiritual practice are 80% more resilient against addiction and depression than those without. Similarly, the Harvard Human Flourishing Program suggests spiritual exercises as a vehicle for flourishing.

Religion and spirituality are complex, and there is much you could attribute positive psychological affect to (serving others, being part of a community, singing together etc). Beyond the community religion creates, spiritual beliefs can also provide a sense of hope that is not rooted in the fortunes of our external circumstances. The psychiatrist Viktor Frankl who was interned in the Nazi concentration camps said that hope was the secret ingredient to getting through the ordeal; those who lacked it very quickly died. Frankl argued that while this was acutely obvious in the concentration camps, it is no less true of life more broadly – hope is something we all need.

This year, Blue Monday happens to coincide with Martin Luther King Day. Martin Luther King is an extraordinary role model for many reasons, and his words have lost none of their power or urgency since he first uttered them. While most of King’s speeches were about justice and civil rights, one line feels particularly fitting for Blue Monday – “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” While Blue Monday might have a spurious scientific origin, there is surely something helpful about deliberately opening up dialogue on what really matters: what does a good life look like? What are the barriers to it? Where are you placing your hope? If nothing else, Blue Monday can provide a nudge to identify our needs and question the systems and assumptions we are ensnared by. That alone feels like a step in the right direction.

More from Culture

©2024 Thinking Faith. All rights reserved. Website by Groundcrew. Privacy Policy

©2024 Thinking Faith. All rights reserved. Website by Groundcrew. Privacy Policy